As a designer, I of course have a desire to make games, but one of my stumbling blocks is programming. Since I never had any formal education in Computer Science (my degree was a Bachelor of Arts in Computer Games Design) this has always been a bit of a hurdle for me when trying to build my own games. But about nine years ago I started digging into how to do this, starting with GameMaker and its own language. I then moved on to Unity, using C#, then Unreal’s Blueprints system, and – more recently – C++ within Unreal. I’ve learned A LOT in that time, but I’ve increasingly felt that I needed a solid Computer Science foundation in order to fully understand some of the inner workings of games which will subsequently help me to program faster and more efficiently without bashing my head against a wall on problems that a lot of programmers will know the answers to quickly and easily. This became more apparent when I recently ran into a problem I’d experienced with Unreal’s AI Navigation system, which required me to delve into the source code, and – while I pretty much solved the issue – it still left me without a full grasp of how its underlying structures and syntax fitted together.

Download the example here: https://pyman.itch.io/wolfenstein-3d-engine

To that end, I embarked on finding quality learning, that aligned with my current level of knowledge but would push my understanding of low-level and foundational Computer Science further and found Gustavo Pezzi’s Wolfenstein Raycasting Course which starts with a JavaScript prototype, then moves into using C for the full implementation of the engine. Building a game from scratch, without an existing engine, is fairly daunting for a typical non-programmer like myself but id Software’s Wolfenstein 3D from 1992 is old enough and simple enough to understand more completely in its entirety even than something like Doom from the following year so it seemed like a good fit. Not too complex, and at my knowledge level, but also pushing me further. The course is mostly about the wall and world rendering, with a section on sprites, so there is no animation, AI, or other game logic within, but that’s fine. I was mostly fascinated with how the raw raycasting algorithm worked.

The final implementation of the engine uses plain old C, the SDL library for basic window handling, and a PNG decoder to load texture data into memory and that’s it, no other libraries or engines used. It’s a pretty magical moment when you create something purely from mathematics that then becomes an entire world on screen.

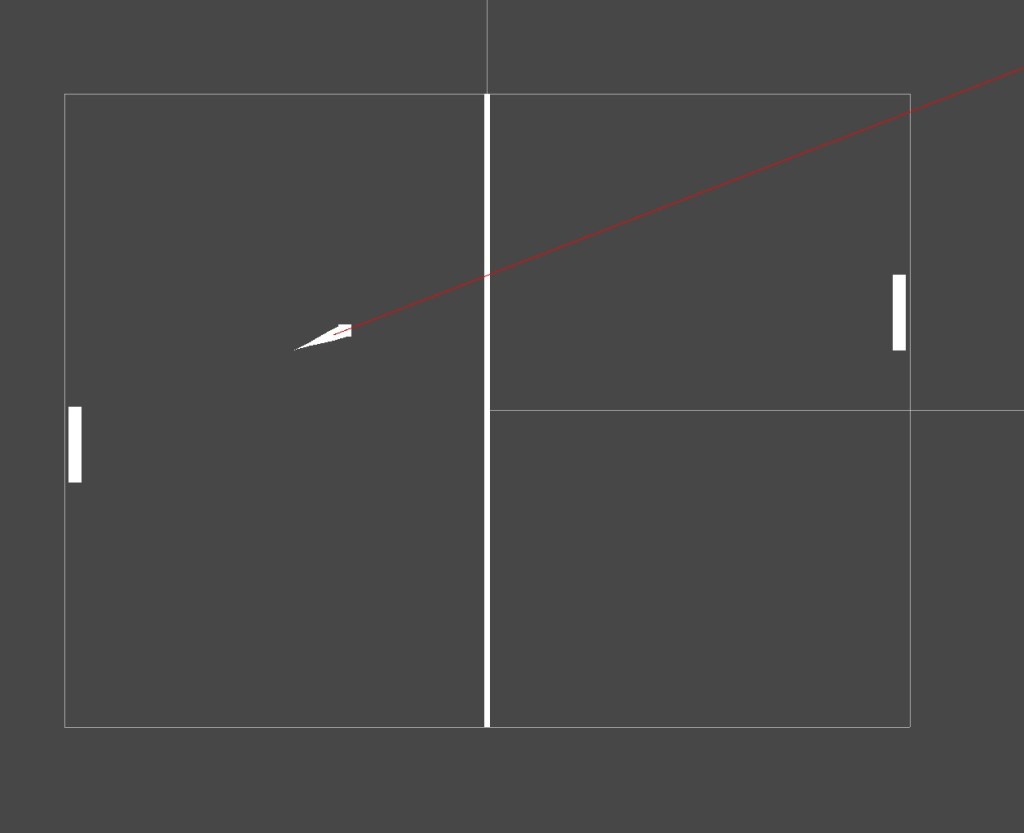

For anyone wondering how it works, the short answer is to pay attention to the minimap in the top left. The player camera is firing a number of rays equivalent to the pixel width of the screen (in this case 800 at a screen res of 800 x 450) within the field of view.

Each ray uses some trigonometry, and good old linear algebra to determine if it’s hitting a grid section that’s a wall or not. If it is, it checks the distance to the wall and vertically scales that pixel column appropriately. It then renders each vertical pixel based on a texture id assigned to the wall and the cartesian coordinates of the texture’s colour data.